Supreme

Danger in the Supreme Court Created by the Federal Constitution

For

those who cherish States’ Rights and American liberties, the day that the

Federal Constitution was ratified and the Articles of Confederation were abandoned

must forever be marked as a day of infamy. This is especially true in the case

of the Federal Supreme Court. It has

laid one burden after another upon the States and American people far beyond the

Tenth Amendment’s intended restrictions: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the

Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States

respectively, or to the people.” The Tenth Amendment and the rest of the

Bill of Rights were intended to pacify the Anti-Federalists who warned that

creating such a Federal Supreme Court (as well as the centralized Federal Government

in general) as conceived in the Federal Constitution would inevitably lead to

Federal over-reach, as well as usurpation of States’ Rights and American

liberties.

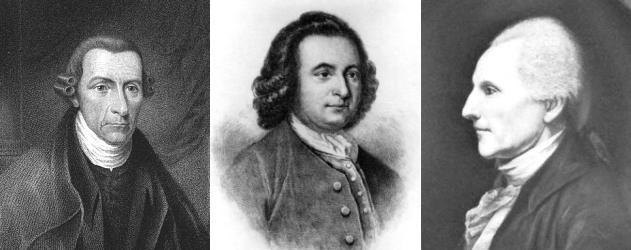

James

Kilpatrick, in his book The Sovereign States: Notes of a Citizen of Virginia

(see http://sovereignstates.org/books/The_Sovereign_States/SovStates_I.html#Isect3

), traces the debate on ratification of the Federal Constitution in the

Virginia Convention which met to decide the question, including the following debate

concerning the Federal Supreme Court:

“Consider, if you will, the

debate on ratification in Virginia. The transcript offers some absorbing

reading…Edmund Pendleton served as

president of the Virginia Convention. He was a remarkable man: lawyer, scholar, statesman,

thinker. In advocating ratification, Pendleton was joined by James Madison,

John Marshall, Edmund Randolph, and Light Horse Harry Lee. They carried the day

against Patrick Henry and George Mason, as leading opponents of the proposition…

Henry

conceived it. He conceived it very clearly. The proposed Constitution, he felt,

was “extremely pernicious, impolitic and dangerous.” He saw no jeopardy to the

people in the Articles of Confederation; he saw great jeopardy in this new

Constitution. And he had this to say:

We are

descended from a people whose government was founded on liberty: Our glorious

forefathers of Great Britain made liberty the foundation of everything. That

country is become a great, mighty and splendid nation; not because their

government is strong and energetic, but, sir, because liberty is its direct end

and foundation. We drew the spirit of liberty from our British ancestors: By

that spirit we have triumphed over every difficulty. But now, sir, the American

spirit, assisted by the ropes and chains of consolidation, is about to convert

this country into a powerful and mighty empire. If you make the citizens of

this country agree to become the subjects of one great consolidated empire of

America, your government will not have sufficient energy to keep them together.

Such a government is incompatible with the genius of Republicanism.(44)

And note this prophetic

observation:

There will be no checks, no real

balances, in this government. What can avail your specious, imaginary balances,

your rope-dancing, chain-rattling, ridiculous ideal checks and contrivances?

What indeed? What have these ideal

checks and balances availed the States in the twentieth century? Henry saw the

empty prospect: “This Constitution is said to have beautiful features; but when

I come to examine these features, sir, they appear to me horribly frightful.

Among other deformities, it has an awful squinting; it squints toward monarchy;

and does not this raise indignation in the breast of every true American?” …

Henry did not imagine that the dual governments

could be kept each within its proper orbit. “I assert that there is danger of

interference,” he remarked, “because no line is drawn between the powers of the

two governments, in many instances; and where there

is a line, there is no check to prevent the one from encroaching upon the

powers of the other. I therefore contend that they must interfere, and that

this interference must subvert the State government as being less powerful.

Unless your government have checks, it must inevitably terminate in the

destruction of your privileges.”

William

Grayson, burly veteran of the Revolution, was another member of the Virginia

convention who clearly perceived the absence of effective checks and balances.

“Power ought to have such checks and limitations,” he said, “as to prevent bad

men from abusing it. It ought to be granted on a supposition that men will be

bad; for it may be eventually so.”(53)

Grayson was here discussing

his apprehensions toward the powers vested by Article III in the Supreme Court

of the United States. “This court,” he protested, “has more power than any

court under heaven.” The court’s appellate jurisdiction, especially, aroused

his alarm: “What has it in view, unless to subvert the State governments?”

But Grayson was not alone in

foreseeing the possibilities of judicial corruption of the Constitution. Even

so stout an advocate of ratification as Governor Randolph admitted strong

doubts and reservations. The court’s jurisdiction was to extend to “all cases

in law and equity . . . arising under the Constitution.” What did the phrase

relate to?

I conceive this to be very

ambiguous. If my interpretation be right, the word “arising” will be carried so

far that it will be made use of to aid and extend the Federal jurisdiction.

Grayson

agreed: “The jurisdiction of all cases arising under the Constitution and the

laws of the Union is of stupendous magnitude. It is impossible for human nature

to trace its extent. It is so vaguely and indefinitely expressed that its

latitude cannot be ascertained.”(54)

True, said Mason: The court’s

jurisdiction “may be said to be unlimited.” He was profoundly disturbed by the

prospect. The greater part of the powers given to the court, he

felt, “are unnecessary, and dangerous, as tending to impair, and ultimately

destroy the State judiciaries, and, by the same principle, the legislation of

the State governments.” Indeed, the court was “so constructed as to destroy the

dearest rights of the community.” Nothing would be left to the State courts:

“Will any gentleman be pleased, candidly, fairly, and without sophistry, to

show us what remains?”

He

continued his criticism of the court’s jurisdiction:

There is no limitation. It

goes to everything. . . . All the

laws of the United States are paramount to the laws and Constitution of any

single State. “The judicial power shall extend to all cases in law and equity

arising under this Constitution.” What objects will not this expression extend

to? . . . When we consider the nature of these courts, we must conclude that

their effect and operation will be utterly to destroy the State governments;

for they will be the judges how far their laws will operate. . . . To what disgraceful and dangerous length does

the principle of this go! . . . The principle itself goes to the destruction of

the legislation of the States, whether or not it was intended.

. . . I think it will destroy the State governments. .

. . There are many gentlemen in the United States who think it right

that we should have one great, national, consolidated government, and that it

was better to bring it about slowly and imperceptibly rather than all at once.

This is no reflection on any man, for I mean none. To those who think that one

national, consolidated government is best for America, this extensive judicial

authority will be agreeable; but I hope there are many in this convention of a

different opinion, and who see their political happiness resting on their State

governments.(55)

It was John Marshall, who

fifteen years later would do so much to justify Mason’s apprehensions, who

undertook to allay his fears now. The Federal government, he insisted,

certainly would not have the power “to make laws on every subject.” Could

members of the Congress make laws affecting the transfer of property, or contracts,

or claims, between citizens of the same State?

Can

they go beyond the delegated powers? If they were to make a law not warranted

by any of the powers enumerated, it would be considered by the judges as an

infringement of the Constitution

which they are to guard. They would not consider such a law as coming under

their jurisdiction. They would declare it void.(56)

Marshall saw no danger to the

States from decrees of the Supreme Court: “I hope that no gentleman will think

that a State will be called at the bar of the Federal court.

. . . It is not rational to suppose that the

sovereign power should be dragged before a court.”(57)

Madison, Monroe, and others

joined Marshall in defending the Third Article. Their debate was long and

detailed. Much of it was concerned with questions of pleading and practice. But

after several days, they went on to other aspects of the Constitution: The

prospect of judicial despotism was recognized by the few, and denied by the

many.”

Anti-Federalists like Patrick

Henry and George Mason of Virginia, as well as those like Samuel Adams in other

States, correctly warned of the consequences, so it is to such as these that we

should now turn and adopt their advice.

The Federal Constitution consolidated too much power in the national

government, and we should return to the Articles of Confederation.

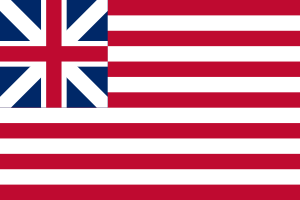

So

we can pray that God would help us bring about the restoration of a

confederated USA of Anglo-American

Patriot

States, under the Articles

of Confederation (America’s first constitution that was unadvisedly and illegally

abandoned), with America’s

first national flag (the Continental Colors or Grand Union flag) as the

symbol of our enterprise:

This

confederated USA can have partitioned out of the USA those liberal “blue” areas

in a sea of “red” areas that remain part of the USA, such as illustrated here:

Facebook

page of the National Effort: https://www.facebook.com/groups/ReturnToArticlesOfConfederation/

Index

of Articles related to this Cause: http://www.puritans.net/articles/indexarticlesconfederation.htm

.